Ghana is currently feeling the heat from a resurgent oil shock, as escalating tensions between Israel and Iran are driving global energy prices sharply upward.

Brent crude, the international benchmark, is climbing from around $65 per barrel in early June to about $75 by mid-month—marking the steepest weekly surge since 2022. Financial analysts, including Goldman Sachs, are projecting that prices could briefly spike to $90–$100 per barrel if the Middle East conflict intensifies. Just weeks ago, forecasts were suggesting a gradual fall in prices towards the low $60s by late 2025.

But in Ghana, where fuel pricing is deregulated, international market shifts are having a direct and near-immediate impact at the pump. The Chamber of Oil Marketing Companies (COMAC) is cautioning that every 10% increase in Brent translates into a similar percentage rise in ex-refinery prices locally.

In fact, Ghana’s energy regulator is initially forecasting a petrol price cut in June—GH¢11.77 per litre—on the back of a strong local currency. However, the sudden surge in global crude prices is reversing that earlier optimism.

Cedi’s Strength Offers Temporary Shield

Amid the global volatility, the Ghanaian cedi is emerging as a surprising stabilizer. It is appreciating sharply, offering consumers a temporary buffer against external fuel shocks. Bloomberg is ranking the cedi among the best-performing currencies worldwide in 2025. From about GH¢15/USD in January, the currency is rising to GH¢10.2 by mid-June—a rebound of nearly 32%.

This strength is being driven by a cocktail of factors: tighter monetary policy from the Bank of Ghana, booming gold export revenues, and sustained confidence in IMF-backed economic reforms. Institutions like Fitch Solutions are forecasting further gains, with the cedi expected to average around GH¢13/USD by the end of 2025.

Thanks to this rebound, petrol and diesel prices are falling by around 6% in early June—a much-needed reprieve for consumers. COMAC is crediting the cedi as the main driver behind the relief, stating that without the appreciation, fuel prices would be significantly higher today.

Fuel Levy Suspended, But Controversy Builds

In an unexpected turn, the government is suspending a proposed GH¢1.00-per-litre Energy Sector Levy that was scheduled to take effect in early June. The decision is being justified on grounds of public pressure and rising global oil prices. President John Dramani Mahama is calling for a reassessment of the levy’s timing in light of recent market instability.

Civil society organizations and policy commentators are weighing in. IMANI’s Franklin Cudjoe is describing the move as “sensible and well-timed,” especially given the unpredictable oil market. However, critics from the opposition are lambasting the government’s handling of the tax, calling it erratic and poorly planned. Former Vice President Dr. Mahamudu Bawumia is warning that the levy would impose a much heavier burden on households compared to the discontinued e-levy—GH¢83 per GH¢1,000 in fuel spending, versus only GH¢10 under the previous tax regime. The minority caucus in parliament is also calling for a complete repeal of the levy under a certificate of urgency.

At the same time, international institutions like the IMF are urging the government to stay the course. They argue that the GH¢1.00 levy will help generate essential revenue to service energy-sector debts and shore up public finances. According to IMF staff, the levy is key to meeting Ghana’s fiscal targets under the ongoing recovery programme.

COMAC’s analysis is illustrating the potential impact clearly: reinstating the levy will raise petrol prices by 9.1% and diesel by 8.3%, pushing average prices from GH¢11.8 to GH¢12.8 and GH¢12.1 to GH¢13.1, respectively. In contrast, if the levy remains off and the cedi maintains strength, June-end prices are likely to decrease by 1–4%.

What the Future Holds: Scenarios and Trade-offs

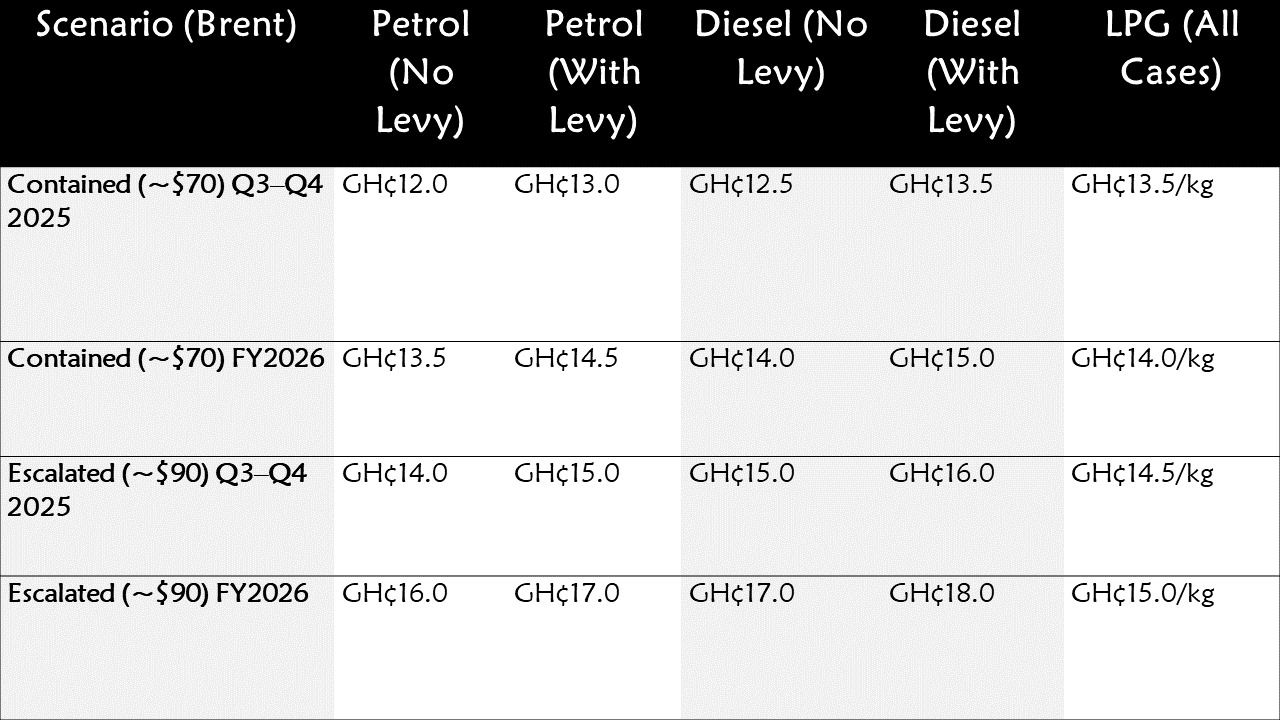

The projections for Ghana’s fuel prices remain closely tied to global markets and exchange rate dynamics. If Brent crude stabilizes around $70 per barrel and the cedi holds firm between GH¢10–12, domestic fuel prices will remain relatively stable, inching only slightly higher by year-end. Under this “contained” scenario, petrol may settle around GH¢12–13/L and diesel at GH¢13–14/L.

But if geopolitical tensions escalate further, pushing oil prices to $90+ and weakening the cedi to GH¢14–15, the picture will shift dramatically. In such a case, petrol prices may spike to GH¢14–16/L and diesel to GH¢15–17/L. Any future reintroduction of the GH¢1 levy would add another cedi per litre across the board. LPG prices, not affected by the levy, would rise only modestly, depending on global conditions.

From a fiscal lens, the suspended levy represents a critical opportunity cost. With annual fuel consumption around 5–6 billion litres, the government could be generating GH¢5–6 billion each year through the levy. That revenue is earmarked for clearing energy-sector debts and reducing fiscal deficits. Each month the levy stays off, several hundred million cedis are being forfeited, creating a budgetary gap that must be filled—either through debt or cuts.

Navigating the Crossroads: Relief vs Reform

Despite its fiscal implications, suspending the levy is providing important economic breathing room for consumers. Fuel taxes already make up nearly 40% of pump prices. Keeping the levy off is helping to contain inflation, ease cost-of-living pressures, and support real household income. With inflation still elevated, analysts are warning that a sudden reintroduction of the tax could reignite inflation expectations.

Currently, the strength of the cedi is helping to suppress imported inflation, and this, in turn, is creating policy space for potential interest rate cuts if inflation continues to decline.

The bigger challenge for Ghanaian policymakers lies in balancing these competing demands: short-term consumer relief versus long-term fiscal sustainability. Experts are advocating for more flexible strategies—such as phasing in the levy when Brent prices fall below certain thresholds or introducing automatic pricing triggers. Beyond taxes, structural energy reforms—especially fixing transmission losses and rationalizing tariffs—will be essential to permanently addressing the root causes of energy-sector debt.

Risks on the global front remain high. A deeper Middle East conflict could propel oil prices past $100 per barrel and weaken the cedi. Conversely, if diplomatic resolutions emerge, and oil prices retreat to the $60s, Ghana could benefit from a period of price stability. Most currency analysts expect the cedi to trend slightly weaker—towards GH¢11–13 by year-end—as capital inflows normalize.

What’s clear is that policymakers will need to remain agile. Oil prices, currency movements, and inflation dynamics are in constant flux. The fuel pricing formula and tax structure may require ongoing adjustment to strike the right balance between protecting consumers and safeguarding fiscal targets.